About Me

- Jeremy

- Web person at the Imperial War Museum, just completed PhD about digital sustainability in museums (the original motivation for this blog was as my research diary). Posting occasionally, and usually museum tech stuff but prone to stray. I welcome comments if you want to take anything further. These are my opinions and should not be attributed to my employer or anyone else (unless they thought of them too). Twitter: @jottevanger

Saturday, June 25, 2011

The LOD-LAM star system....

Mia yesterday posted a question to the MCG list asking for reactions to the scheme, which addresses in particular the issue of rights and rights statements for metadata - both the nature of the licence, which must reach a minimum level of openness, and the publication of that licence/waiver. Specifically she asked whether the fact that even the minimum one-star rating required data to be available for both non-commercial and commercial use was a problem for institutions.

My reply was that I felt it essential, in order for it to count as linked data (so I'm very pleased to see it required for the most basic level of conformance). But here I'd like to expand on that a bit and also start to tease out a distinction that I think has been somewhat ignored: between the use of data to infer, reason, search, analyse, and the re-publication of data.

First, the commercial/non-commercial question. I suppose one could consider that as long as the data isn't behind a paywall or password or some other barrier then it's open, but that's not my view: I think that if it's restricted to a certain group of users then it's not open. Placing requirements on those users (e.g. attribution) is another matter; that's a limitation (and a pain, perhaps) but it's not closing the data off per se, whereas making it NC only is. Since the 4 different star levels in the LOD-LAM scheme all seem to reflect the same belief that's cool with me.

The commercial use question is a problem that has bedevilled Europeana in recent months, and so it is a very live issue in my mind. The need to restrict the use of the metadata to non-commercial contexts absolutely cripples the API's utility and undermines efforts to create a more powerful, usable, sustainable resource for all, and indeed to drive the creative economy in the way that the Europeana Commission originally envisaged. With a bit of luck and imagination this won't stay a problem for long, because a new data provider agreement will encourage much more permissive licences for the data, and in the meantime a subset of data with open licences (over 3M objects) has been partitioned off and was released this very week as Linked Open Data. Hurrah!

This brings us to the question of how LOD is used and whether we need a more precise understanding of how this might relate to the restrictions (e.g. non-commercial only) and requirements (e.g. giving attribution) that could be attached to data. I see two basic types of usage of someone else's metadata/content: publication e.g. displaying some facts from a 3rd party LOD source in your application; and reasoning with the data, whereby you may use data from 3rd party A to reach data from 3rd party B, but not necessarily republish any of the data from A.

If LOD sources used for reasoning have to be treated in the same way as those used for publication you potentially have a lot more complexity to deal with*, because every node involved in a chain of reasoning needs to be checked for conformance with whatever restrictions might apply to the consuming system. When a data source might contain data with a mixture of licences, so you have to check each piece of data, this is pretty onerous and will make developers think twice about following any links to that resource, so it's really important that aggregators like Culture Grid and Europeana can apply a single licence to a set of data.

If, on the other hand, licences can be designed that apply only to republication, not to reasoning, then client systems can use LOD without having to check that commercial use is permitted for every step along the way, and without having to give attribution to each source regardless of whether it’s published or not. I'm not sure that Creative Commons licences are really set up to allow for this distinction, although ODC-ODbL might be. Besides, if data is never published to a user interface, who could check whether it had been used in the reasoning process along the way? If my application finds a National Gallery record that references Pieter de Hooch’s ULAN record (just so that we’re all sure we’re talking about the same de Hooch), and I then use that identifier to query, say, the Amsterdam Museum dataset, does ULAN need crediting? Here ULAN is used only to ensure co-reference, of course. What if I used the ULAN record’s statement that he was active in Amsterdam between 1661-1684 to query DBPedia and find out what else happened in Amsterdam in the years that he was active there? I still don’t republish any ULAN data, but I use it for reasoning to find the data I do actually publish. At what point am I doing something that requires me to give attribution, or to be bound by restrictions on commercial use? Does the use of ULAN identifiers for co-reference bind a consuming system to the terms of use of ULAN? I guess not, but between this and republishing the ULAN record there’s a spectrum of possible uses.

Here's an analogy: when writing a book (or a thesis!), if one quotes from someone else's work they must be credited - and if it's a big enough chunk you may have to pay them. But if someone's work has merely informed your thinking, perhaps tangentially, and you don't quote them; or if perhaps you started by reading a review paper and end up citing only one of the papers it directed you to, then there's not the same requirement to either seek their permission to use their work, nor to credit them in the reference list. There's perhaps a good reason to try to do so, because it gives your own work more authority and credibility if you reference sources, but there's not a requirement - in fact it's sometime hard to find a way to give the credit you wish to someone who's informed your thinking! As with quotations and references, so with licensing data: attributing the source of data you republish is different to giving attribution to something that helped you to get somewhere else; nevertheless, it does your own credibility good to show how you reached your conclusions.

Another analogy: search engines already adopt a practical approach to the question of rights, reasoning and attribution. "Disallow: /" in a robots.txt file amounts to an instruction not to index and search (reason) and therefore not to display content. If this isn't there, then they may crawl your pages, reason with the data they gather, and of course display (publish) it in search results pages. Whilst the content they show there is covered by "fair use" laws in some countries, in others that’s not the case so there has occasionally been controversy about the "publication" part of what they do, and it has been known for some companies to get shirty with Google for listing their content (step forward, Agence France, for this exemplary foot-shooting). As far as attribution goes, one could argue that this happens through the simple act of linking to the source site. When it comes to the reasoning part of what search engines do, though, there's been no kerfuffle concerning giving attribution for that. No one minds not being credited for their part in the page rank score of a site they linked to – who pays it any mind at all? – and yet this is absolutely essential to how Google and co. work. To me, this seems akin to the hidden role that linked data sources can play in-between one another.

Of course, the “reasoning” problem has quite a different flavour depending upon whether you’re reasoning across distributed data sources or ingesting data into a single system and reasoning there. As Mia noted, the former is not what we tend to see at the moment. All of the good examples I know of digital heritage employing LOD actually use it by ingesting the data and integrating it into the local index, whether that's Dan Pett's nimble PAS work or Europeana's behemoth. But that doesn't mean that it's a good idea for us to build a model that assumes this will always be the case. Right now we're in the earliest stages of the LOD/semweb project really gathering pace - which I believe it finally is. People will do more ambitious things as the data grows, and the current pragmatic paradigm of identifying a data source that could be good for enriching your data and ingesting it into your own store where you can index it and make it actually scale may not stay the predominant one. It makes it hard to go beyond a couple of steps of inference because you can't blindly follow all the links you find in the LOD you ingest and ingest them too – you could end up ingesting the whole of the web of data. As the technology permits and the idea of making more agile steps across the semantic graph beds in I expect we'll see more solutions appear where reasoning is done according to what is found in various linked data sources, not according to what a system designer has pre-selected. As the chains of inference grow longer, the issue of attribution becomes keener, and so in the longer term there will be no escaping the need to be able to reason without giving attribution.

This is the detail we could do with ironing out in licencing LOD, and I’d be pleased to see it discussed in relation to the LOD-LAM star scheme.

Monday, October 18, 2010

Open Culture 2010 ruminations #1: Linked Data

Linked (Open) Data was a constant refrain at the meetings (OK, not at the WP1 meeting) and the conference, and two things struck me. Firstly, there’s still lots of emphasis on creating out-bound links and little discussion of the trickier(?) issue of acting as a hub for inbound links, which to my mind is every bit as important. Secondly, there’s a lot of worry about persuading content providers that it’s the right thing to do. Now the very fact that it was a topic of conversation probably means that there really is a challenge there, and it’s worth then taking some time to get our ducks in a row so we can lay out very clearly to providers why it is not going to bring the sky crashing down on their heads.

During a brainstorming session on Linked Data, the table I sat with paid quite a lot of attention to this latter issue of selling the idea to institutions. The problem needs teasing apart, though, because it has several strands – some of which I think have been answered already. We were posed the questions “Is your institution technically ready for Linked Data” and “Does it have a business issue with LD?”, but we wondered if it’s even relevant if the institution is technically ready: Europeana’s technical ability is the question, and it can step into the breach for individual institutions that aren't technically ready yet. With regard to the "business issue" question, one wonders whether such issues are around out-going links, or incoming links? Then, for inbound linkage, is it the actual fact of linkage, or the metadata at the end of the link that are more likely to be problematic? And what are people’s worries about outbound links?

What we resolved it down to in the end was that we expected people would be most worried about (a) their content being “purloined”, and (b) links to poor-quality outside data sources. But how new are these worries? Not new at all, is the answer, and Linked Data really does nothing to make them more likely to be realised, when you think about what we already enable. In fact, there’s a case to be made that not only does LD increase business opportunities but it might also increase organisations’ control over “their” data, and improve the quality of things that are done with it: letting go of your data means people don’t do a snatch-and-grab instead.

Ultimately, I think, Linked Data really doesn’t need a sales effort of its own. If Europeana has won people over to the idea of an API and the letting-go of metadata that it implies, then Linked Data is nothing at all to worry about. What does it add to what the API and HTML pages already do? Two things:

- A commitment to giving resources a URI (for all intents and purposes, read “stable URL”), which they should have for the HTML representation anyway. In fact, the HTML page could even be at that URI and either contain the necessary data as, say, RDFa in the HTML, or through content negotiation offer it in some purer data format (say, EDM-XML).

- Links to other data sources to say “this concept/thing is the sameAs that concept/thing”. People or machines can then optionally either say “ah, I know what you mean now”, or go to that resource to learn more. Again, links are as old as the Web and, not to labour the point, are kinda implicit in its name.

So really there’s little reason to worry, especially if the API argument has already been put to bed. However I thought it might be an idea to list some ways in which we can translate the idea of LD so it’s less scary to decision-makers.

- Remember the traditional link exchange? There’s nothing new in links, and once upon a time we used to try to arrange link exchanges like a babysitting circle or something. We desperately wanted incoming links, so where’s the reason in now saying, “we’re comfortable linking out, but don’t want people linking in to our data”?

- Linked data as SEO. Organisations go to great lengths to optimise their sites so they fare well in search engine rankings. In other words, we already encourage Google, Bing and the like spider, copy and index our entire websites in the name of making them easier to discover. Now, search is fine, but it would be still better to let people use our content in more places (that’s what the API is about), and Linked Data acts like SEO for applications that could do that: if other resources link to ours, applications will “visit”.

The other thing here is that we let search engines take our content for analysis, knowing they won’t use it for republication. We should also licence our content for complete ingestion so that applications indexing it can be as powerful as possible. - It’s already out there, take control! We let go of our content the moment we put it on the web, and we all know that doing that was not just a good thing, it’s the only right thing. But whilst the only way to use it is cut-n-paste (a) it’s not reused and seen nearly as much as it should be, and (b) it’s completely out of our control, lacking our branding and “authority”, and not feeding people back to us. Paradoxically, if we make it easier to reuse our content our way than it is to cut and paste, we can change this for the better: maintain the link with the rest of our content, keep intellectual ownership, drive people back to us. Helping reuse through linked data and APIs thus potentially gives us more control.

- Get there first. There is no doubt that if we don’t offer our own records of our things in a reusable form online then bit by bit others will do it for us, and not in the way we might like. Wikipedia/DBPedia is filling up with records of artworks great and small, and will therefore be the reference URIs for many objects.

- Your objects as context. Linked data lets us surround things/concepts with context;

So if I think fears about LD should something of a non-issue, what do I think are the more important questions we should be worrying about? Basically, it’s all about what’s at the end of the reference URI and what we can let people do with it. Again, it’s really a question as much about the API as it is about Linked Data, but it’s a question Europeana needs to bottom out. How we license the use of data we’re releasing from the bounds of our sites is going to become a hotter area of debate, I reckon, with issues like:

- Is Europeana itself technically prepared to offer its contents as resources for use in the LD web? Are we ready to offer stable URIs and, where appropriate, indicate the presence of alternative URIs for objects?

- What entities will Europeana do this for? Is it just objects (relatively simple because they are frequently unique), or is it for concepts and entities that may have URIs elsewhere?

- What’s the right licence for simple reuse?

- Does that licence apply to all data fields?

- Does it apply to all providers’ data?

- Does it apply to Europeana-generated enrichments?

- Who (if anyone) gets the attribution for the data? The provider? Aggregator? Disseminator (Europeana)?

- Do we need to add legal provisions for static downloads of datasets as opposed to dynamic, API-based use of data?

Just to expand a little on the last item, the current nature of semantic web (or SW-like) applications is that the tricky operation of linking the data in your system to that in another isn't often done on the fly: often it happens once and the results ingested and indexed. Doing a SPARQL query over datasets on opposite sides of the Atlantic is a slow business you don’t want to repeat for every transaction, and joining more sets than that is something to avoid. The implication of this is that, if a third party wanted to work with a graph that spread across Europeana and their own dataset, it might be much more practical for them to ingest the relevant part of the Europeana dataset and index and query it locally. This is in contrast to the on-the-fly usage of the metadata which I suspect most people have in mind for the API. Were we be allow data downloads we might wish to add certain conditions to what they could do with the data beyond using it for querying.

In short I think most of the issues around Linked Data and Europeana are just issues around opening the data full stop. LD adds nothing especially problematic beyond what an API throws up, and in fact it's a chance to get some payback for that because it facilitates inbound links. But we need to get our ducks in a row to show organisations that there's little to be worried about and a lot to gain from letting Europeana get on with it.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Linked Data meeting at the Collections Trust

[UPDATE, March 2010: Richard Light's presentation is now available here]

On February 22nd Collections Trust hosted a meeting about Linked Data (LD) at their London Bridge offices. Aside from yours truly and a few other admitted newbies amongst the very diverse set of people in the room, there was a fair amount of experience in LD-related issues, although I think only a few could claim to have actually delivered the genuine article to the real world. We did have two excellent case studies to start discussion, though, with Richard Light and Joe Padfield both taking us through their work. CT's Chief Executive Nick Poole had invited Ross Parry to chair and tasked him with squeezing out of us a set of principles from which CT could start to develop a forward plan for the sector, although it should be noted that they didn’t want to limit things too tightly to the UK museum sector.

In the run-up to the meeting I’d been party to a few LD-related exchanges, but they’d mainly been concentrated into the 140 characters of tweets, which is pragmatic but can be frustrating for all concerned, I think. The result was that the merits, problems, ROI, technical aspects etc of LD sometimes seemed to disappear into a singularity where all the dimensions were mashed into one. For my own sanity, in order to understand the why (as well as the how) of Linked Data, I hoped to see the meeting tease these apart again as the foundation for exploring how LD can serve museums and how museums can serve the world through LD. I was thinking about these as axes for discussion:

- Creating vs consuming Linked Data

- End-user (typically, web) vs business, middle-layer or behind-the-scenes user

- Costs vs benefits. ROI may be thrown about as a single idea, but it’s composed of two things: the investment and the return.

- On-the-fly use of Linked Data vs ingested or static use of Linked Data

- Public use vs internal drivers

To start us off, Richard Light spoke about his experiments with the Wordsworth Trust’s ModesXML database (his perennial sandbox), taking us through his approach to rendering RDF using established ontologies, to linking with other data nodes on the web (at present I think limited to GeoNames for location data, grabbed on the fly), and to cool URIs and content negotiation. Concerning ontologies, we all know the limitations of Dublin Core but CIDOC-CRM is problematic in its own way (it’s a framework, after all, not a solution), and Richard posed the question of whether we need any specific “museum” properties, or should even broaden the scope to a “history” property set. He touched on LIDO, a harvesting format but one well placed to present documents about museum objects and which tries to act as a bridge between North American formats (CDWALite) and European initiatives including CIDOC-CRM and SPECTRUM (LIDO intro here, in depth here (both PDF)). LIDO could be expressed as RDF for LD purposes.

For Richard, the big LD challenges for museums are agreeing an ontology for cross-collection queries via SPARQL; establishing shared URLs for common concepts (people, places, events etc); developing mechanisms for getting URLs into museum data; and getting existing authorities available as LD. Richard has kindly allowed me to upload his presentation Adventures in Linked Data: bringing RDF to the Wordsworth Trust to Slideshare.

Joe Padfield took us through a number of semantic web-based projects he’s worked on at the National Gallery. I’m afraid I was too busy listening to take many notes, but go and ferret out some of his papers from conferences or look here. I did register that he was suggesting 4store as an alternative to Sesame for a triple store; that they use a CRM-based data model; that they have a web prototype built on a SPARQL interface which is damn quick; and that data mining is the key to getting semantic info out of their extensive texts because data entry is a mare. A notable selling point of SW to the “business” is that the system doesn’t break every time you add a new bit of data to the model.

Beyond this, my notes aren’t up to the task of transcribing the discussion but I will put down here the things that stuck with me, which may be other peoples’ ideas or assertions or my own, I’m often no longer sure!

My thoughts in bullet-y form

I’m now more confident in my personal simplification that LD is basically about an implementation of the Semantic Web “up near the surface”, where regular developers can deploy and consume it. It seems like SW with the “hard stuff” taken out, although it’s far from trivial. It reminds me a lot of microformats (and in fact the two can overlap, I believe) in this surfacing of SW to, or near to, the browsable level that feels more familiar.

Each audience to which LD needs explaining or “selling” will require a different slant. For policy makers and funders, the open data agenda from central government should be enough to encourage them that (a) we have to make our data more readily available and (b) that LD-like outputs should be attached as a condition to more funding; they can also be sold on the efficiency argument or doing more with less, avoiding the duplication of effort and using networked information to make things possible that would otherwise not be. For museum directors and managers, strings attached to funding, the “ethical” argument of open data, the inevitability argument, the potential for within-institution and within-partnership use of semantic web technology; all might be motives for publishing LD, whilst for consuming it we can point to (hopefully) increased efficiency and cost savings, the avoidance of duplication etc. For web developers, for curators and registrars, for collections management system vendors, there are different motives again. But all would benefit from some co-ordination so that there genuinely is a set of services, products and, yes, data upon which museums can start to build their LD-producing and –consuming applications.

There was a lot of focus on producing LD but less on consuming it; more than this, there was a lot of focus producing linkable data i.e. RDF documents, rather than linking it in some useful fashion. It's a bit like that packaging that says "made of 100% recyclable materials": OK, that's good, but I'd much rather see "made of 100% recycled materials". All angles of attack should be used in order to encourage museums to get involved. I think that the consumption aspect needs a bit of shouting about, but it also could do with some investment from organisations like Collections Trust that are in a position potentially to develop, certify, recommend, validate or otherwise facilitate LD sources that museums, suppliers etc will feel they can depend upon. This might be a matter of partnering with Getty, OCLC or Wikipedia/dbPedia to open up or fill in gaps in existing data, or giving a stamp of recommendation to GeoNames or similar sources of referenceable data. Working with CMS vendors to make it easy to use LD in Modes, Mimsy, TMS, KE EMu etc, and in fact make it more efficient than not using LD; now that would make a difference. The benefits depend upon an ecosystem developing, so bootstrapping that is key.

SPARQL: it ain’t exactly inviting. But then again I can’t help but feel that if the data was there, we knew where to find it and had the confidence to use it, more museum web bods like me would give it a whirl. The fact that more people are not taking up the challenge of consuming LD may be partly down to this sort of technical barrier, but may also be to do with feeling that the data are insecure or unreliable. Whilst we can “control” our own data sources and feel confident to build on top of them, we can’t control dbPedia etc., so lack confidence of building apps that depend on them (Richard observed that dbPedia contains an awful lot of muddled and wrong data, and Brian Kelly's recent experiment highlighted the same problem). In the few days since the meeting there have been more tweets in this subject, including references to this interesting looking Google Code project for a Linked Data API to make it simpler to negotiate SPARQL. With Jeni Tennison as an owner (who has furnished me with many an XSLT insight and countless code snippets) it might actually come to something.

Tools for integrating LD into development UIs for normal devs like me – where are they?

If LD in cultural heritage needs mass in order for people to take it up, then as with semantic web tech in general we should not appeal to the public benefit angle but to internal drivers: using LD to address needs in business systems, just as Joe has shown, or between existing partners.

What do we need? Shared ontologies, LD embedded in software, help with finding data sources, someone to build relationships with intermediaries like publishers and broadcasters that might use the LD we could publish.

Outcomes of the meeting

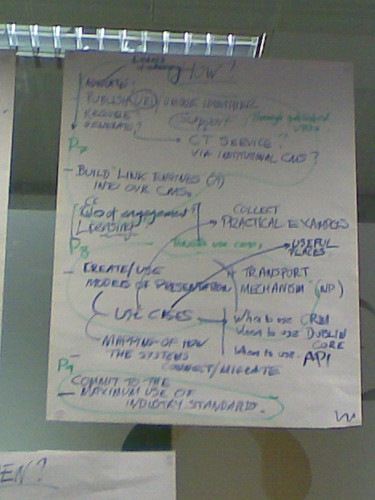

So what did we come up with as a group? Well Ross chaired a discussion at the end that did result in a set of principles. Hopefully we'll see them written up soon coz I didn't write them down, but they might be legible on these images: