[UPDATE, March 2010: Richard Light's presentation is now available here]

On February 22nd Collections Trust hosted a meeting about Linked Data (LD) at their London Bridge offices. Aside from yours truly and a few other admitted newbies amongst the very diverse set of people in the room, there was a fair amount of experience in LD-related issues, although I think only a few could claim to have actually delivered the genuine article to the real world. We did have two excellent case studies to start discussion, though, with Richard Light and Joe Padfield both taking us through their work. CT's Chief Executive Nick Poole had invited Ross Parry to chair and tasked him with squeezing out of us a set of principles from which CT could start to develop a forward plan for the sector, although it should be noted that they didn’t want to limit things too tightly to the UK museum sector.

In the run-up to the meeting I’d been party to a few LD-related exchanges, but they’d mainly been concentrated into the 140 characters of tweets, which is pragmatic but can be frustrating for all concerned, I think. The result was that the merits, problems, ROI, technical aspects etc of LD sometimes seemed to disappear into a singularity where all the dimensions were mashed into one. For my own sanity, in order to understand the why (as well as the how) of Linked Data, I hoped to see the meeting tease these apart again as the foundation for exploring how LD can serve museums and how museums can serve the world through LD. I was thinking about these as axes for discussion:

- Creating vs consuming Linked Data

- End-user (typically, web) vs business, middle-layer or behind-the-scenes user

- Costs vs benefits. ROI may be thrown about as a single idea, but it’s composed of two things: the investment and the return.

- On-the-fly use of Linked Data vs ingested or static use of Linked Data

- Public use vs internal drivers

To start us off, Richard Light spoke about his experiments with the Wordsworth Trust’s ModesXML database (his perennial sandbox), taking us through his approach to rendering RDF using established ontologies, to linking with other data nodes on the web (at present I think limited to GeoNames for location data, grabbed on the fly), and to cool URIs and content negotiation. Concerning ontologies, we all know the limitations of Dublin Core but CIDOC-CRM is problematic in its own way (it’s a framework, after all, not a solution), and Richard posed the question of whether we need any specific “museum” properties, or should even broaden the scope to a “history” property set. He touched on LIDO, a harvesting format but one well placed to present documents about museum objects and which tries to act as a bridge between North American formats (CDWALite) and European initiatives including CIDOC-CRM and SPECTRUM (LIDO intro here, in depth here (both PDF)). LIDO could be expressed as RDF for LD purposes.

For Richard, the big LD challenges for museums are agreeing an ontology for cross-collection queries via SPARQL; establishing shared URLs for common concepts (people, places, events etc); developing mechanisms for getting URLs into museum data; and getting existing authorities available as LD. Richard has kindly allowed me to upload his presentation Adventures in Linked Data: bringing RDF to the Wordsworth Trust to Slideshare.

Joe Padfield took us through a number of semantic web-based projects he’s worked on at the National Gallery. I’m afraid I was too busy listening to take many notes, but go and ferret out some of his papers from conferences or look here. I did register that he was suggesting 4store as an alternative to Sesame for a triple store; that they use a CRM-based data model; that they have a web prototype built on a SPARQL interface which is damn quick; and that data mining is the key to getting semantic info out of their extensive texts because data entry is a mare. A notable selling point of SW to the “business” is that the system doesn’t break every time you add a new bit of data to the model.

Beyond this, my notes aren’t up to the task of transcribing the discussion but I will put down here the things that stuck with me, which may be other peoples’ ideas or assertions or my own, I’m often no longer sure!

My thoughts in bullet-y form

I’m now more confident in my personal simplification that LD is basically about an implementation of the Semantic Web “up near the surface”, where regular developers can deploy and consume it. It seems like SW with the “hard stuff” taken out, although it’s far from trivial. It reminds me a lot of microformats (and in fact the two can overlap, I believe) in this surfacing of SW to, or near to, the browsable level that feels more familiar.

Each audience to which LD needs explaining or “selling” will require a different slant. For policy makers and funders, the open data agenda from central government should be enough to encourage them that (a) we have to make our data more readily available and (b) that LD-like outputs should be attached as a condition to more funding; they can also be sold on the efficiency argument or doing more with less, avoiding the duplication of effort and using networked information to make things possible that would otherwise not be. For museum directors and managers, strings attached to funding, the “ethical” argument of open data, the inevitability argument, the potential for within-institution and within-partnership use of semantic web technology; all might be motives for publishing LD, whilst for consuming it we can point to (hopefully) increased efficiency and cost savings, the avoidance of duplication etc. For web developers, for curators and registrars, for collections management system vendors, there are different motives again. But all would benefit from some co-ordination so that there genuinely is a set of services, products and, yes, data upon which museums can start to build their LD-producing and –consuming applications.

There was a lot of focus on producing LD but less on consuming it; more than this, there was a lot of focus producing linkable data i.e. RDF documents, rather than linking it in some useful fashion. It's a bit like that packaging that says "made of 100% recyclable materials": OK, that's good, but I'd much rather see "made of 100% recycled materials". All angles of attack should be used in order to encourage museums to get involved. I think that the consumption aspect needs a bit of shouting about, but it also could do with some investment from organisations like Collections Trust that are in a position potentially to develop, certify, recommend, validate or otherwise facilitate LD sources that museums, suppliers etc will feel they can depend upon. This might be a matter of partnering with Getty, OCLC or Wikipedia/dbPedia to open up or fill in gaps in existing data, or giving a stamp of recommendation to GeoNames or similar sources of referenceable data. Working with CMS vendors to make it easy to use LD in Modes, Mimsy, TMS, KE EMu etc, and in fact make it more efficient than not using LD; now that would make a difference. The benefits depend upon an ecosystem developing, so bootstrapping that is key.

SPARQL: it ain’t exactly inviting. But then again I can’t help but feel that if the data was there, we knew where to find it and had the confidence to use it, more museum web bods like me would give it a whirl. The fact that more people are not taking up the challenge of consuming LD may be partly down to this sort of technical barrier, but may also be to do with feeling that the data are insecure or unreliable. Whilst we can “control” our own data sources and feel confident to build on top of them, we can’t control dbPedia etc., so lack confidence of building apps that depend on them (Richard observed that dbPedia contains an awful lot of muddled and wrong data, and Brian Kelly's recent experiment highlighted the same problem). In the few days since the meeting there have been more tweets in this subject, including references to this interesting looking Google Code project for a Linked Data API to make it simpler to negotiate SPARQL. With Jeni Tennison as an owner (who has furnished me with many an XSLT insight and countless code snippets) it might actually come to something.

Tools for integrating LD into development UIs for normal devs like me – where are they?

If LD in cultural heritage needs mass in order for people to take it up, then as with semantic web tech in general we should not appeal to the public benefit angle but to internal drivers: using LD to address needs in business systems, just as Joe has shown, or between existing partners.

What do we need? Shared ontologies, LD embedded in software, help with finding data sources, someone to build relationships with intermediaries like publishers and broadcasters that might use the LD we could publish.

Outcomes of the meeting

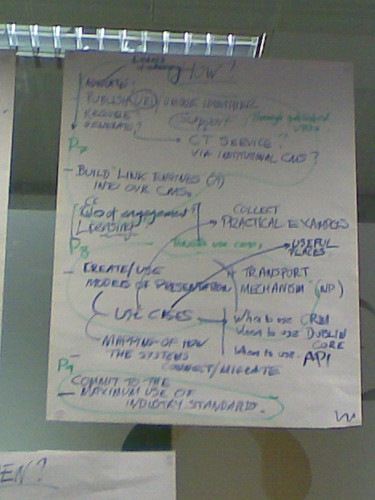

So what did we come up with as a group? Well Ross chaired a discussion at the end that did result in a set of principles. Hopefully we'll see them written up soon coz I didn't write them down, but they might be legible on these images: