About Me

- Jeremy

- Web person at the Imperial War Museum, just completed PhD about digital sustainability in museums (the original motivation for this blog was as my research diary). Posting occasionally, and usually museum tech stuff but prone to stray. I welcome comments if you want to take anything further. These are my opinions and should not be attributed to my employer or anyone else (unless they thought of them too). Twitter: @jottevanger

Saturday, June 25, 2011

The LOD-LAM star system....

Mia yesterday posted a question to the MCG list asking for reactions to the scheme, which addresses in particular the issue of rights and rights statements for metadata - both the nature of the licence, which must reach a minimum level of openness, and the publication of that licence/waiver. Specifically she asked whether the fact that even the minimum one-star rating required data to be available for both non-commercial and commercial use was a problem for institutions.

My reply was that I felt it essential, in order for it to count as linked data (so I'm very pleased to see it required for the most basic level of conformance). But here I'd like to expand on that a bit and also start to tease out a distinction that I think has been somewhat ignored: between the use of data to infer, reason, search, analyse, and the re-publication of data.

First, the commercial/non-commercial question. I suppose one could consider that as long as the data isn't behind a paywall or password or some other barrier then it's open, but that's not my view: I think that if it's restricted to a certain group of users then it's not open. Placing requirements on those users (e.g. attribution) is another matter; that's a limitation (and a pain, perhaps) but it's not closing the data off per se, whereas making it NC only is. Since the 4 different star levels in the LOD-LAM scheme all seem to reflect the same belief that's cool with me.

The commercial use question is a problem that has bedevilled Europeana in recent months, and so it is a very live issue in my mind. The need to restrict the use of the metadata to non-commercial contexts absolutely cripples the API's utility and undermines efforts to create a more powerful, usable, sustainable resource for all, and indeed to drive the creative economy in the way that the Europeana Commission originally envisaged. With a bit of luck and imagination this won't stay a problem for long, because a new data provider agreement will encourage much more permissive licences for the data, and in the meantime a subset of data with open licences (over 3M objects) has been partitioned off and was released this very week as Linked Open Data. Hurrah!

This brings us to the question of how LOD is used and whether we need a more precise understanding of how this might relate to the restrictions (e.g. non-commercial only) and requirements (e.g. giving attribution) that could be attached to data. I see two basic types of usage of someone else's metadata/content: publication e.g. displaying some facts from a 3rd party LOD source in your application; and reasoning with the data, whereby you may use data from 3rd party A to reach data from 3rd party B, but not necessarily republish any of the data from A.

If LOD sources used for reasoning have to be treated in the same way as those used for publication you potentially have a lot more complexity to deal with*, because every node involved in a chain of reasoning needs to be checked for conformance with whatever restrictions might apply to the consuming system. When a data source might contain data with a mixture of licences, so you have to check each piece of data, this is pretty onerous and will make developers think twice about following any links to that resource, so it's really important that aggregators like Culture Grid and Europeana can apply a single licence to a set of data.

If, on the other hand, licences can be designed that apply only to republication, not to reasoning, then client systems can use LOD without having to check that commercial use is permitted for every step along the way, and without having to give attribution to each source regardless of whether it’s published or not. I'm not sure that Creative Commons licences are really set up to allow for this distinction, although ODC-ODbL might be. Besides, if data is never published to a user interface, who could check whether it had been used in the reasoning process along the way? If my application finds a National Gallery record that references Pieter de Hooch’s ULAN record (just so that we’re all sure we’re talking about the same de Hooch), and I then use that identifier to query, say, the Amsterdam Museum dataset, does ULAN need crediting? Here ULAN is used only to ensure co-reference, of course. What if I used the ULAN record’s statement that he was active in Amsterdam between 1661-1684 to query DBPedia and find out what else happened in Amsterdam in the years that he was active there? I still don’t republish any ULAN data, but I use it for reasoning to find the data I do actually publish. At what point am I doing something that requires me to give attribution, or to be bound by restrictions on commercial use? Does the use of ULAN identifiers for co-reference bind a consuming system to the terms of use of ULAN? I guess not, but between this and republishing the ULAN record there’s a spectrum of possible uses.

Here's an analogy: when writing a book (or a thesis!), if one quotes from someone else's work they must be credited - and if it's a big enough chunk you may have to pay them. But if someone's work has merely informed your thinking, perhaps tangentially, and you don't quote them; or if perhaps you started by reading a review paper and end up citing only one of the papers it directed you to, then there's not the same requirement to either seek their permission to use their work, nor to credit them in the reference list. There's perhaps a good reason to try to do so, because it gives your own work more authority and credibility if you reference sources, but there's not a requirement - in fact it's sometime hard to find a way to give the credit you wish to someone who's informed your thinking! As with quotations and references, so with licensing data: attributing the source of data you republish is different to giving attribution to something that helped you to get somewhere else; nevertheless, it does your own credibility good to show how you reached your conclusions.

Another analogy: search engines already adopt a practical approach to the question of rights, reasoning and attribution. "Disallow: /" in a robots.txt file amounts to an instruction not to index and search (reason) and therefore not to display content. If this isn't there, then they may crawl your pages, reason with the data they gather, and of course display (publish) it in search results pages. Whilst the content they show there is covered by "fair use" laws in some countries, in others that’s not the case so there has occasionally been controversy about the "publication" part of what they do, and it has been known for some companies to get shirty with Google for listing their content (step forward, Agence France, for this exemplary foot-shooting). As far as attribution goes, one could argue that this happens through the simple act of linking to the source site. When it comes to the reasoning part of what search engines do, though, there's been no kerfuffle concerning giving attribution for that. No one minds not being credited for their part in the page rank score of a site they linked to – who pays it any mind at all? – and yet this is absolutely essential to how Google and co. work. To me, this seems akin to the hidden role that linked data sources can play in-between one another.

Of course, the “reasoning” problem has quite a different flavour depending upon whether you’re reasoning across distributed data sources or ingesting data into a single system and reasoning there. As Mia noted, the former is not what we tend to see at the moment. All of the good examples I know of digital heritage employing LOD actually use it by ingesting the data and integrating it into the local index, whether that's Dan Pett's nimble PAS work or Europeana's behemoth. But that doesn't mean that it's a good idea for us to build a model that assumes this will always be the case. Right now we're in the earliest stages of the LOD/semweb project really gathering pace - which I believe it finally is. People will do more ambitious things as the data grows, and the current pragmatic paradigm of identifying a data source that could be good for enriching your data and ingesting it into your own store where you can index it and make it actually scale may not stay the predominant one. It makes it hard to go beyond a couple of steps of inference because you can't blindly follow all the links you find in the LOD you ingest and ingest them too – you could end up ingesting the whole of the web of data. As the technology permits and the idea of making more agile steps across the semantic graph beds in I expect we'll see more solutions appear where reasoning is done according to what is found in various linked data sources, not according to what a system designer has pre-selected. As the chains of inference grow longer, the issue of attribution becomes keener, and so in the longer term there will be no escaping the need to be able to reason without giving attribution.

This is the detail we could do with ironing out in licencing LOD, and I’d be pleased to see it discussed in relation to the LOD-LAM star scheme.

Thursday, June 09, 2011

Hack4Europe London, by your oEmbedded reporter

oEmbed for Europeana

I took with me a few things I'd worked on already and some ideas of what I wanted to expand. One that I'd got underway involved oEmbed.

If you haven't come across it before, oEmbed is a protocol and lightweight format for accessing metadata about media. I've been playing with it recently, weighing it up against MediaRSS, and it really has its merits. The idea is that you can send a URL of a regular HTML page to an oEmbed endpoint and it will send you back all you need to know to embed the main media item that's on that page. Flickr, YouTube and various other sites offer it, and I'd been playing with it as a means of distributing media from our websites at IWM. Its main advantages are that it's lightweight, usually available as JSON (ideally with callbacks, to avoid cross-domain issues), and most importantly of all, that media from many different sites are presented in the same form. This makes it

easier to mix them up. MediaRSS is also cool, holds multiple objects (unlike oEmbed), and is quite widespread.

I've made a javascript library that lets you treat MediaRSS and oEmbed the same so you can mix media from lots of sources as generic media objects, which seemed like a good starting point for taking Europeana content (or for that matter IWM content) and contextualising it with media from elsewhere. The main thing missing was an oEmbed service for Europeana. What you have instead is an OpenSearch feed (available as JSON, but without the ability to return a specific item, and without callbacks) and a richer SRW record for individual items. This is XML only. Neither option is easily mapped to common media attributes, at least not to the casual developer, so before the hackday I knocked together a simple oEmbed service. You send it the URL of the item you like on Europeana, it sends back a JSON representation of the media object (with callback, if specified), and you're done.(Incidentally I also made a richer representation using Yahoo! Pipes, which meant that the SRW was available as JSON too.)

Using the oEmbed

With a simple way of dealing with just the most core data in the Europeana record, I was then in a position to grab it "client-side" with the magic of jQuery. I'm still in n00b status with this but getting better, so I tried a few things out.

Inline embedding

First, I put simple links to regular Europeana records onto an HTML page, gave them a class name to indicate what they were, and then used jQuery to gather these and get the oEmbed. This was used to populate a carousel (too ugly to link to). An alternative also worked fine: adding a class and "title" tag to other elements. Kind of microformatty. Putting YouTube and Flickr links on the same page then results in a carousel that mixes of all of them up.

Delicious collecting

Then I bookmarked a bunch of Europeana records into Delicious and tagged them with a common tag (in my case, europeanaRecord). I also added my own note to each bookmark so I could say why I picked it. With another basic HTML page (no server-side nonsense for this) I put jQuery to work again to:

- grab the feed for my tag as JSON

- submit each link in the feed to my oEmbed service

- add to the resulting javascript object (representing a media object) a property to hold the note I put with my bookmark

- put all of these onto another pig-ugly page*, and optionally assemble them into a carousel (click the link at the top). When you get half a dozen records or more this is worthwhile. This even uglier experiment shows the note I added in Delicious attached to the item from Europeana, on the fly in your browser.

I suppose what I was doing was test driving use-cases for two enhancements to Europeana's APIs. The broader was about the things one could do if and when there is a My Europeana API. My Europeana is the user and community part of the service, and at some point one would hope that things that people collect, annotate, tag, upload etc will be accessible through a read/write API for reuse in other contexts. Whilst waiting for a UGC API, though, I showed myself that one can use something as simple as Delicious to do the collecting and add some basic UGC to it (tags and note). The narrower enhancement would be an oEmbed service, and oddly I think it's this narrower one that came out stronger, because it's so easy to see how it can help even duffer coders like me in mixing up content from multiple sources.

I didn't

What I didn't manage to do, which I'd hoped to try, was hook up bookmarking somehow with the Mashificator, which would complete the circle quite nicely, or get round to using the enriched metadata that Europeana has now made available including good period and date terms, lots of geo data, and multilingual annotations. These would be great for turning a set of Delicious bookmarked records into a timeline, a map, a word-cloud etc. Perhaps that's next. And finally, it would be pretty trivial to create oEmbed services for various other museum APIs I know and to make mixing up their collection on your page as easy as this, with just a bit of jQuery and Delicious.

Working with Jan

Earlier in the day I spent some time working with Jan Molendijk, Europeana's Technical Director, working on some improvements to a mechanism he's built for curating search results and outputting static HTML pages. It's primarily a tool for Europeana's own staff but I think we improved the experience of assembling/curating a set, and again I got to strech my legs a little with jQUery, learning all the time. He decided to use Delicious too to hold searches, which themselves can be grouped by tags and assembled into super-sets of sets. It was a pleasure and a privilege to work with the driving force behind Europeana's technical team; who better to sit by than the guy responsible for the API?

*actually this one uses the Yahoo! Pipe coz the file using the oEmbed is a bit of a mess still but it does the same thing

Friday, April 29, 2011

What are they building in there?

The work of the New Media department at the IWM is very complex at the moment, as it has been since I started almost a year ago. We're now a pretty large department and I'm not deeply involved in all aspects of what we do, but we're also a tight team and I think we all keep an eye on what's happening in other areas - which is great and necessary, but sometimes it all gets pretty confusing! Part of our team needs to focus on keeping our existing sites going a little longer, but they too are also working on the new developments. So with so much going on I thought I'd step back for a moment and try to lay it out for my own benefit as much as anyone's - it's very easy to get lost in the many strands of activity.

- a new mechanism (and UI) for aggregating, preparing and delivering collections content

- the ongoing effort to improve our collections metadata (not our work, of course)

- a wide-ranging e-commerce programme (which runs for well over a year after we relaunch the sites)

- a realignment of IWM's identity

- a refresh of multimedia throughout our branches

- overhauling our web hosting

- and finally, sorting out our development environment and re-thinking how we work (not a project but a big effort)

Some other departments have had to make considerable efforts so that the road-maps for the projects they own align with our own, and thanks to those efforts I think we're going to be able to deliver most of what we hoped to and maybe some extras when we launch, but of course that will just be the start of a rolling programme of improvement. We will start, for instance, with temporary solutions to some of our e-commerce provision. It's an intricate dance where we try to avoid doing things twice or, still worse, do things badly, but we also try to avoid being so dependent upon doing something perfectly (or that's out of our control) that we risk failing to deliver anything. For this reason we're limiting our ambitions concerning e-commerce to improving integration at a superficial level but postponing deeper integration such as unified shopping baskets and the like.

For me there are quite a few learning curves involved in all of this. I've got thin experience with the LAMP stack (we're using most or all of this, at least in our development environment - live O/S TBC), and nil with Drupal (we're using D7 for the core sites). My experience of working as part of a team of developers is also limited and has taken place in purely Microsoft environments, whereas we're adopting agile techniques and using tools like Jira/Greenhopper and SVN (no more Visual Source Safe) to help in this. The infrastructure at IWM is quite different to my old haunt, too, and finding my way round that, finding out even what I needed to know and how to get it done has taken pretty much until now. We do now have a development environment we can work with, though, both internally and with third parties, and in due course I hope to understand it! Besides that, there's the ongoing activity of researching and testing new solutions and practices, which is always fascinating, sometimes frustrating, and generally time-consuming.

So the new website will be in Drupal 7, although we may continue to use WordPress for blogs (WP3 is another new one for me). We were treading a fine line by choosing to use version 7, a decision we made a few weeks before the betas and, finally, RC1 came out, but we're feeling vindicated. Because some modules still have quite a few wrinkles there are some blockages (Media Module anyone?), but on the whole we feel it was a risk worth taking - there are major benefits in this version, and D6 will be retired well before D7. So when bugs have come up, Monique and Toby (the two Drupal devs we're so lucky to have working on this) have been balancing their efforts in working around problems, contributing fixes, and putting things on hold until patches are available. They've undertaken a fair amount of custom work where essential and we have a lot of functionality in place ready for theming. Design and theme development are taking place out-of-house, though, so the next few weeks should be interesting!

[June note: and so it has proved]

Lots of our thinking is around integration, of course, both to do now and in readiness for future developments. There's a lot around discovery and whilst I've not been anywhere near as involved with Drupal development as I'd like, I've been doing some of the work on search. We'll be using separate Solr cores to index Drupal content, e-shop products, collections metadata, stock photography, and a variety of non-Drupal/legacy IWM sites (indexed with Nutch). This will support an imperfect, loosely-coupled sort of integration, one that we can improve bit by bit.

Our strategy for delivering collections-related content builds on the software that we commissioned from Knowledge Integration when I was at the Museum of London. That conceptual approach and architecture (which I'll save for another post) was one idea I was really eager to bring with me to IWM, but I have to admit I found my advocacy skills seriously lacking when it came to explaining the case for it. All the same, we got there in the end and I believe that there's a growing understanding of the benefits of the approach, both immediately and in the long term - and now that we're making real progress with implementation confidence is growing that we can do what we promised. Phase 1 is strictly limited in any case, so that we have what we need for the website launch and that's it; Phase 2 will have the fun stuff - the enrichment, contextualisation, and nice things for developers - and we'll start building other things on top of the mechanism too, because of course the website is but one front-end.

[June note: K-Int have packaged up the software into a product which they launched at the recent OpenCulture exhibition. Very well worth checking out.]

That's where I got to. Will add more soon. Suffice to say that things remain quite busy but that we do at least now have a newly-skinned e-shop which teething problems aside looks a damn sight better than before, thanks to the efforts of Christian, Wendy, Kieran and Garry "The Bouncing Ball" Taylor.

Wednesday, March 02, 2011

links wot caught my eye #6

- Transcribing handwritten documents. A very useful compilation of projects using digitised handwritten documents, including some fine examples of how transcription has been done and of technology you can use if you're doing the same. (Google Docs, you probably need to sign in)

- A/B testing (Read Write Web). We're thinking about following the Powerhouse Museum's lead and trying some A/B testing when we launch our new websites. I'd been considering using an ad server to try some of this (and because it could do other things in terms of serving up content dynamically) but really these look like a better place to start.

- Outta the box geo shiz with OSGeo4W. I've looked before at GRASS, got as far as downloading it and then chickened out. Well I just realised that the people responsible for it also run a project to package GRASS and a bunch of other GIS-related software into an easy, Windows-friendly installation package/interface. It makes it a doddle to find an install a wide variety of such tools to let you do everything from tile making to map service creation to web map serving.

That said, GRASS is still not easy to jump into for the geo-noob, and if you don't have anyone to hold your hand then one of the challenges of map-related software is to work out exacxtly what jobs you need to accomplish to get where you want to go, and then to find out which software will do that job for you. I can't really help you there but reading aroung the OSGeo site will.

Tuesday, March 01, 2011

links wot caught my eye #5

- New insights into the 1641 Irish Rebellion revealed (AHRC) and more (Past Horizons) A nice example of what digital analysis of texts now makes possible. As the article says, and quite aside from the interest of the results themselves, doing this sort of analysis would have been a lifetime's work previously. Needless to say, IWM has a large quantity of texts. I'm just itching to see what digital humanists could do with a sample of them - once duly digitised, of course.

- Europeana's API available. This is great news, albeit it not without caveats, chiefly that access is limited to Europeana's network of non-commercial partners (there are about 1500 of them). Although I knew that the issue of data licences for API usage was unresolved after November's plenary I suppose I'd assumed that it must have been fixed. But then, that's no small order: getting that number of data providers to sign up to anything is a massive challenge, and I'm glad that Europeana decided that, rather than letting this hold up the API, they'd launch it for a more limited audience initially and work on the recalcitrant partners. I'd recommend reading David Haskiya's blog post for an informative Q&A on the what and why of the API launch.

I played with the alpha of the API last year and put together the Mashificator with it, but you can see several other examples of it in use here. - And in more Europeana news, EuropeanaConnect is the geeking heart of #Europeana. It's EuropeanaTech conference in Vienna, October shd be good http://bit.ly/fRH5Df [to plagiarise my own tweet]

- Oh and finally, I see that DISH2011 is in the planning. It will be in December this year and from what I heard of the last DISH in 2009 it should be well worth attending. Keep an eye here for news

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

links wot caught my eye, #4 of n

- Augmented Reality Field Trips & the 150th Anniversary of the U.S. Civil War - ReadWriteWeb. For us, the start of the First World War is the big looming anniversary, but in the US the Civil War is also hugely significant, and the 150th is anniversary is pretty much here. I'll be keeping an eye on how it's marked to see if there are ideas we can port over for three years hence.

- Internet Archive Partners With 150 Libraries to Launch an E-Book Lending Program - also RWW. I worry that, whilst e-book lending may take off, it's going to be hard for libraries to come up with a proposition that makes them the place to go in order to borrow. I wish them well but can't help thinking of Canute's legendary demonstration of inevitability

- Interim report card on O'Reilly's IT transformation insights into the progress they're making in transforming IT inside (perhaps) the world's greatest IT publisher

- AR browsers - RWW again. Argon looks kind of Layar-like but I like the idea of Argon-enabling a regular website with a few lines of code (whatever that means). I still don't know what Daqri is but I guess if it gains traction we'll all find out.

Friday, February 18, 2011

links wot...#3 of n

OK not a lot in this one but I may as well get it out there.

- Whither social search?

O'Reilly Radar is getting together with Bing to cover the future of search, which they promise to cover much more widely than just Bing. Just up, here's a video here that frames the idea of social search and gives an idea of the sort of future Bing, and probably many others, envisage for letting us make the most of the wisdom of our network. - Digging words

From the same source, you should also check out the interview about WordSeer. Digital heritage scholars, check it out and have a go at the heat mapping. I tried the word "cane", seems as good as any. This is very timely for me, given that I spent this morning discussing how to make a neglected archive of potentially immense historical value work for us and for scholars through digitisation. When you have a mile of shelves groaning with typed transcripts, there's a clear use-case for powerful tools like this.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

links wot...#2 of n

Easy and Cheap Authoring for the Microsoft Kinect with Open Exhibits - Ideum

Yet again, cool stuff from Ideum. Their core OpenExhibits multitouch software is free to museums and the like, and now here's a plugin to make it work with Microsoft's Kinect interface. Niiice.

Mission: Explore (link to OS blog)

Kids to entertain over half term? Want something vaguely educational/stimulating but not dull for them to do? Looks like there are some good ideas courtesy of Mission: Explore

"Internet of things" links

For some reason I've seen several articles using the phrase "Internet of things" these last few days - it's not new but I guess it's trending (like the word "trending"). Here are some:

- Mobile Phones Will Serve as Central Hub to "Internet of Things" - ReadWriteWeb

Some interesting figures and observations, and the idea of the mobile phone in this role makes ever more sense. It has identity, multiple communications protocols, mobility and flexibility, ubiquity, ever more power... Figures. - Thingworx (HT TechCrunch)

Although the thin TechCrunch regurgitated press release thing mentioned "internet of things" I'm still not very clued in on WTF this is. Your imagination can run wild when faced with such imprecise claims, but still, it could be interesting. The most important news from the TC perspective, of course, is that they have Series B funding. Phew. - Mobile, social, being in the world with the ‘Internet of things’ - Mariamz

Finally, an orthogonally different meaning of the phrase, but a most interesting one (and nothing to do with gadgets). The Mariamz perspective is always unique!

links wot caught my eye lately. Number 1 in a series of n>=1

RWW on Alfreso's approach to managing the gushing torrent of social data. "Content is the conversation".

"Alfresco's push is also part of its strategic adoption of CMIS, an open standard for integrating content into enterprise environments. This allows Alfresco to integrate with IBM's Lotus Quickr and Drupal as two examples."

oEmbed

I've not really registered this one before. A standard to enable systems to work out how to address a request for information about image and video resources so that they can be embedded elsewhere. Or something. Thinking, this does something significantly different to MediaRSS that could be useful for us in opening up our content for reuse. Shame there's nothing for audio in it, the reason seems to be for culpably UI-related reasons. Where's the separation of data from presentation? But otherwise, interesting

Geni - introduction for developers

Geni is a freemium family-tree building web app which aims to "build the world's family tree" or some such. Of course, this is somewhat stymied by the fact that users' trees can, quite rightly, be kept private. But nevertheless the tools are there for linking them together. The existence of an API makes it particularly interesting, even if coverage is poor at present. I guess one could just use it to explore the data you have put in yourself.

How to licence research data - DCC

Clearly this isn't the same problem as how to licence museum collection metadata but it's in the same problem space. It's an issue that few people have really tackled properly yet, at least not in its full implications - it's easy enough to tack a CC-BY licence to something in theory, but how does an organisation really find the right balance between enabling/encouraging reuse, and ensuring that the data are kept up to date, accurate, and (possibly) attributed when no longer on their own digital properties? I don't know the answer, but whilst we're waiting for the issues to be discussed properly this sort of white paper may be the best proxy to get us thinking along the right lines. I think at least there are some instructive analogies to be found here, as well as some stuff that helped clarify legal areas I was confused about.

Saturday, November 27, 2010

When should I give a toss about open source-i-ness?

Open source, or just the assurance of knowing there’s a fire exit nearby? What's more important to a museum?

I've never really got into the debate about open source software because, well, I can't really get into it. Sure, there are philosophical aspects that ring my bell a little bit, and there are pragmatic aspects too, but I don't have a feeling that using open source software is the only morally acceptable answer so, overall, I'm ambivalent. Ambivalence (or nuance?) makes for poor polemic, which OSS advocates never lack.

All the same it does often nag at me that I should bring together the strands of my thoughts, if only because the cheerleaders of open source software have such an easy case to make! And on the contrary side, those that use less open alternatives sometimes seem obliged to take oppositional defensive stances attacking OSS on principle: an equally bullshit attitude.

Clearly there is a philosophical question about the right of software developers to own and limit access to software; a right which is in direct opposition to OSS. Personally I think there's nothing morally wrong with asking people to pay for something you made, although obviously I think there's plenty that’s morally right about giving it away! There are people who think that buying software from a company is Inherently Wrong, or that buying it without having the right and ability to modify the source-code is objectionable and a dereliction of duty. I think merely that it's a bad idea quite a bit of the time. I think this, not because it's immoral to pay for software that you can't do with exactly as you will, but because practically speaking it may expose you to costs or risks that you should try to avoid.

So bollocks to the principle, what about the practical? At least that lets us have a discussion. There’s the question of having access to the source code, as well as permission to mess with it. Now I don’t know about you, but for me this has never been a strong reason to use Linux. I have less than zero intention or likelihood of getting under the bonnet of any flavour of Linux and messing with the source, any more than I’d learn C in order to rewrite PHP itself for my own idiosyncratic needs. The further up the stack you come, the more likely I am to want access to the source – there’s perhaps a 10-20% chance we at IWM might have to mess with the Drupal core at some level (undesirable as that may seem), as we implement our new CMS; and if I can ever get my head round Java I might even one day try to contribute to the development of Solr (realistically that’s more like a 1% chance). So it’s all about what bit of the stack you’re talking about, but much of the time diving into the source is only a very theoretical possibility.

Of course freely-licensed source code also means that others can tinker with it, and this may be a good thing – someone else can make you your personalised Linux distro, perhaps? Also, for better or worse, you do tend to see products fork. Sometimes this is managed well by packaging up the diversification in modules that share a common core – this can become a bit of a nightmare of conflict management, but it’s got its merits too. Again, PHP or Drupal are examples. If nothing else it’s a nice fall-back if you know that the source is open, just in case the product is dropped by its owner (or community). And on occasion closed code has been thrown open, sometimes with great success – see Mozilla, which emerged from Netscape and took off.

How about the community? Well as usual this is a multi-level thing. If you want a community of support for the users of a product, this is not just the preserve of open source. Sometimes OSS develops a huge community of users contributing extensions, plugins etc, and sometimes it doesn’t, and it’s the same for non-OSS. Lots of Adobe or Microsoft products and platforms have massive communities around them and the sheer volume of expertise, of problems-already-solved, around the implementation or use of a product might be more important than the need to change the product itself. Once again, it’s about what you or your organisation really needs, and the potential cost of compromise.

How about the question of ownership? If a commercial company has control over the roadmap and licensing terms of some mission-critical software are you not exposing your organisation by using it? Perhaps, yes, and sometimes it’s clear that OSS can buffer you from this risk, but other times we can get a nasty surprise. MySQL is now owned by Oracle. A bunch of changes to the licence happened this autumn, and whilst Oracle might be positioning MySQL for a more enterprise-scale future its suddenly possible to pay an awful lot for a licence, depending upon your needs. And Java? Sun owns this. It’s meant to be open source too, but ownership of the standard is complex and there’s an almighty struggle going on, with the Apache Foundation finding itself suddenly looking quite weak in the battle for control of the language that underlies most of its flagship products. And now we wonder, is even Linux going to end up open to a Microsoft attack? Some people worry that it could, following the sale of Novell. Symbian has been deserted by all its partners and is now being killed off by Nokia. If you want the Symbian source so you can plough your own furrow/fork your own eye-balls, you’d better grab it about now.

This is simply to say: the merits of OSS aren’t uniformly distributed, they’re not necessarily always of great importance in a given scenario, and sometimes they may not be worth the cost of those benefits. Cost and benefit is what should matter to a museum, not the politics of software development and ownership.

To be fair I should also mention the downsides of non-open sourced software, but for expediency I’ll just say: potentially any and all of the risks for OSS mentioned above and some more.

For instance, although it’s a truism to say that what is good for the consumer is good for business it’s not that simple - business. I need only say “DRM” to make the point (although where it’s been foisted upon music consumers they have voted against it and seen a partial roll-back) [edit 14/12/10: semi-relevant XKCD image follows]

The noxious Windows verification software which stops you from changing the configuration of your machine extensively – who asked for that except for Billg? A road-map determined by profit maximisation therefore doesn’t always seem to coincide with what the users want – see also Apple’s slow striptease of technology when they introduce some new gizmo-porn for an example. You want expandable memory with that? GPS? Video? You’ll have to wait a generation or two, perhaps forever.

Then there’s buying licences. At MoL we used Microsoft’s CMS2002, and in truth I’d had relatively little problem with the source-code being closed – it seemed to do what we wanted, had the power of .Net available to extend it, and there was little obvious need to mess with the “closed” parts. We got the software at a trivial price (about 1% of Percussion’s ticket price at the time, I think), but that wasn’t to last. CMS2002 was initially marketed alongside SharePoint Portal Server, but in due course the two were integrated into MOSS2007. When CMS2002 was taken off the market the only way to buy a licence for it was to get a MOSS2007 licence, and this (being a much bigger application) was about 10 times the price. Still cheap compared to much paid-for competition but no longer trivial. I wouldn’t have wanted to use MOSS2007 even if we had the resources to migrate the code but that’s what we had to buy and then downgrade the licence. I’d never even thought about the issue of licences being taken off the market, but of course if you want to add another production server (as we did) you have to buy what they’re selling. In principle they could have chosen not even to sell us an alternative or asked whatever they liked. Now that was a lesson for me, and that’s a genuine reason for avoiding products where licenses are at the discretion of a vendor.

So what really matters?

OK, so there’s a debate to be had over when it’s right and important to go open source. Is it a tool, or a platform? Does it offer you a fire-exit so you can take your stuff elsewhere? What’s the total cost of ownership? Have you sold your soul? And blah blah blah.

Most of the time, though, a more pertinent question is how one procures custom applications. Throughout my time as a museum web person I have always sought to ensure that when a custom application was built for us we required the source code (and other files) and the right to modify, reuse and extend that code. We didn’t necessarily require a standard open source licence (difficult for all sorts of reasons), but enough openness for us to remain, practically speaking, independent of the supplier once the software was delivered. On rare occasions pragmatism has compromised this – for instance, when we used System Simulation’s Index+ to power Museum of London’s Postcodes site – with mixed results. In the latter case, we got a great application but one that we couldn’t really support ourselves nor afford to have SSL support adequately (a side effect of project funding).

The wrap

So, when should a museum use open source software? I don’t have the answer to that, but I do say that if there’s a principle that museums should follow it’s the principle of pragmatic good management, and the politics or ethical “rightness” of (F)OSS should give way to this. I’d always try to get custom applications built and licensed in a way that enables other people to maintain and extend them. And I’d select software or platforms by taking a list that looks something like the following and seeing how it applied to that specific software, to my organisations own situation and to the realities of what we’d want to be able to do with the software in the expected lifecycle of the system.

OSS goodness:

- Access to the source so you can fiddle with it yourself

- Access to the source so others can fiddle and you aren’t in thrall to a software co.

- Free stuff

and potentially:

- A community of like-minded developers working together to make what you, the users, want

- Greater sustainability?

- lack of roadmap or leadership

- lack of clear ownership

- lack of support contracts

- poorly integrated code, add-ons/modules etc

proprietary goodness:

- all the stuff OSS can be bad at...

- sometimes, great communities of users and people who develop on top of the software

Finally, stuff I like to see but which may be present or absent from either open or proprietary software:

- Low total cost of ownership

- Known life-cycle/roadmap for several years ahead

- A clear exit strategy: open standards, comprehensive cross-compatible export mechanism

- Flexible licence, ability to buy future licences!

- Ability to change the code...sometimes

- Confidence that, if the version I want to use gets left behind, I’ll be able to take it forward myself, or do so with a bunch of others

- Not-caringness of the software: if it’s something I could do with one tool or another and really not care, then I’m free to migrate as I please. I don’t care that, say, PhotoShop isn’t open source because if it doesn’t do what I want or I can’t afford to put it on my new workstation I’ll use something else, and nothing too bad will happen

Jesus. Can I blame ambivalence for my long-windedness? Please don’t answer that.

P.S. At IWM we are shifting to a suite of open-source applications for our new websites. Some are familar to me, some entirely new, but it's a good time to make the jump - a clean slate. I'm very excited.

Thursday, November 04, 2010

The Mashificator: comments please!

Seb Chan from the Powerhouse Museum (one of the APIs I used) was kind enough to do an e-mail interview with me for his Fresh + New(er) blog. If you don't know his blog, you really should.

Monday, October 18, 2010

Open Culture 2010 ruminations #2: Europeana, UGC and the API, plus a bit of "what are we here for?"

Some background: Jill Cousins, Europeana's Director, outlined the four objectives that drive project/service/network/dream (take your pick), which go approximately like this:

- To Aggregate – bringing everything together in one place, interoperable, rich (or rich enough) and multilingual

- To Facilitate – to encourage innovation in digital heritage, to stimulate the digital economy, to bring greater understanding between the people of Europe, to build an amazing network of partners and friends

- To Distribute – code, data, content

- To Engage – to put the content into forms that engage people, wherever they may be and however they want to use it

A key plank in the distribution strategy is the API. For engagement, an emerging social strategy includes opportunities for users to react to and create content themselves, and to channel the content to external social sites (Facebook and the like). Both of these things are too big to go into here, but I think one thing we haven't got covered properly is the overlap between the two. Channeling content to people on 3rd party sites ticks the "distribution" box but whilst that in iteself may be engaging it is not the same as being "social" or facilitating UGC there. If people have to come to our portal to react they simply won't. In other words, our content API has to be accompanied by a UGC API - read and write. Even if the "write" part does nothing more than allow favouriting and tagging it will make it possible to really engage with Europeana from Facebook etc.

What falls out of this is my answer to one of Stefan Gradmann's questions to WP3 (the technical working party). Stefan asked, do we want to recommend that work progresses on authentication/authorization mechanisms (OAuth/OpenID, Shibboleth etc) for the Danube release (July 2011)? My answer is a firm "yes". Until that is sorted out we can't have a "social" API to support Europeana's engagement objective off-site, and if such interaction not possible off-site then we're really not making the most of the "distribution" strand either.

Open Culture 2010 ruminations #1: Linked Data

Linked (Open) Data was a constant refrain at the meetings (OK, not at the WP1 meeting) and the conference, and two things struck me. Firstly, there’s still lots of emphasis on creating out-bound links and little discussion of the trickier(?) issue of acting as a hub for inbound links, which to my mind is every bit as important. Secondly, there’s a lot of worry about persuading content providers that it’s the right thing to do. Now the very fact that it was a topic of conversation probably means that there really is a challenge there, and it’s worth then taking some time to get our ducks in a row so we can lay out very clearly to providers why it is not going to bring the sky crashing down on their heads.

During a brainstorming session on Linked Data, the table I sat with paid quite a lot of attention to this latter issue of selling the idea to institutions. The problem needs teasing apart, though, because it has several strands – some of which I think have been answered already. We were posed the questions “Is your institution technically ready for Linked Data” and “Does it have a business issue with LD?”, but we wondered if it’s even relevant if the institution is technically ready: Europeana’s technical ability is the question, and it can step into the breach for individual institutions that aren't technically ready yet. With regard to the "business issue" question, one wonders whether such issues are around out-going links, or incoming links? Then, for inbound linkage, is it the actual fact of linkage, or the metadata at the end of the link that are more likely to be problematic? And what are people’s worries about outbound links?

What we resolved it down to in the end was that we expected people would be most worried about (a) their content being “purloined”, and (b) links to poor-quality outside data sources. But how new are these worries? Not new at all, is the answer, and Linked Data really does nothing to make them more likely to be realised, when you think about what we already enable. In fact, there’s a case to be made that not only does LD increase business opportunities but it might also increase organisations’ control over “their” data, and improve the quality of things that are done with it: letting go of your data means people don’t do a snatch-and-grab instead.

Ultimately, I think, Linked Data really doesn’t need a sales effort of its own. If Europeana has won people over to the idea of an API and the letting-go of metadata that it implies, then Linked Data is nothing at all to worry about. What does it add to what the API and HTML pages already do? Two things:

- A commitment to giving resources a URI (for all intents and purposes, read “stable URL”), which they should have for the HTML representation anyway. In fact, the HTML page could even be at that URI and either contain the necessary data as, say, RDFa in the HTML, or through content negotiation offer it in some purer data format (say, EDM-XML).

- Links to other data sources to say “this concept/thing is the sameAs that concept/thing”. People or machines can then optionally either say “ah, I know what you mean now”, or go to that resource to learn more. Again, links are as old as the Web and, not to labour the point, are kinda implicit in its name.

So really there’s little reason to worry, especially if the API argument has already been put to bed. However I thought it might be an idea to list some ways in which we can translate the idea of LD so it’s less scary to decision-makers.

- Remember the traditional link exchange? There’s nothing new in links, and once upon a time we used to try to arrange link exchanges like a babysitting circle or something. We desperately wanted incoming links, so where’s the reason in now saying, “we’re comfortable linking out, but don’t want people linking in to our data”?

- Linked data as SEO. Organisations go to great lengths to optimise their sites so they fare well in search engine rankings. In other words, we already encourage Google, Bing and the like spider, copy and index our entire websites in the name of making them easier to discover. Now, search is fine, but it would be still better to let people use our content in more places (that’s what the API is about), and Linked Data acts like SEO for applications that could do that: if other resources link to ours, applications will “visit”.

The other thing here is that we let search engines take our content for analysis, knowing they won’t use it for republication. We should also licence our content for complete ingestion so that applications indexing it can be as powerful as possible. - It’s already out there, take control! We let go of our content the moment we put it on the web, and we all know that doing that was not just a good thing, it’s the only right thing. But whilst the only way to use it is cut-n-paste (a) it’s not reused and seen nearly as much as it should be, and (b) it’s completely out of our control, lacking our branding and “authority”, and not feeding people back to us. Paradoxically, if we make it easier to reuse our content our way than it is to cut and paste, we can change this for the better: maintain the link with the rest of our content, keep intellectual ownership, drive people back to us. Helping reuse through linked data and APIs thus potentially gives us more control.

- Get there first. There is no doubt that if we don’t offer our own records of our things in a reusable form online then bit by bit others will do it for us, and not in the way we might like. Wikipedia/DBPedia is filling up with records of artworks great and small, and will therefore be the reference URIs for many objects.

- Your objects as context. Linked data lets us surround things/concepts with context;

So if I think fears about LD should something of a non-issue, what do I think are the more important questions we should be worrying about? Basically, it’s all about what’s at the end of the reference URI and what we can let people do with it. Again, it’s really a question as much about the API as it is about Linked Data, but it’s a question Europeana needs to bottom out. How we license the use of data we’re releasing from the bounds of our sites is going to become a hotter area of debate, I reckon, with issues like:

- Is Europeana itself technically prepared to offer its contents as resources for use in the LD web? Are we ready to offer stable URIs and, where appropriate, indicate the presence of alternative URIs for objects?

- What entities will Europeana do this for? Is it just objects (relatively simple because they are frequently unique), or is it for concepts and entities that may have URIs elsewhere?

- What’s the right licence for simple reuse?

- Does that licence apply to all data fields?

- Does it apply to all providers’ data?

- Does it apply to Europeana-generated enrichments?

- Who (if anyone) gets the attribution for the data? The provider? Aggregator? Disseminator (Europeana)?

- Do we need to add legal provisions for static downloads of datasets as opposed to dynamic, API-based use of data?

Just to expand a little on the last item, the current nature of semantic web (or SW-like) applications is that the tricky operation of linking the data in your system to that in another isn't often done on the fly: often it happens once and the results ingested and indexed. Doing a SPARQL query over datasets on opposite sides of the Atlantic is a slow business you don’t want to repeat for every transaction, and joining more sets than that is something to avoid. The implication of this is that, if a third party wanted to work with a graph that spread across Europeana and their own dataset, it might be much more practical for them to ingest the relevant part of the Europeana dataset and index and query it locally. This is in contrast to the on-the-fly usage of the metadata which I suspect most people have in mind for the API. Were we be allow data downloads we might wish to add certain conditions to what they could do with the data beyond using it for querying.

In short I think most of the issues around Linked Data and Europeana are just issues around opening the data full stop. LD adds nothing especially problematic beyond what an API throws up, and in fact it's a chance to get some payback for that because it facilitates inbound links. But we need to get our ducks in a row to show organisations that there's little to be worried about and a lot to gain from letting Europeana get on with it.

Sunday, October 03, 2010

Internet Archive and the URL shortener question

So ealier this week @tmtn tweeted from the Royal Society

"Penny-drop moment. If bit.ly goes belly up, all the links we've used it for, break."and there followed a little exchange about what might be done to help - the conclusion being, I think, not a lot. For your own benefit you might export a list of your links as HTML or OPML (as you can from Delicious, which does link shortening now), but for whoever else has your links there's no help.

But it got me thinking about how the Internet Archive might fit in. Schachter mentions archiving the databases of link shortening services, and here's one home for them that really could help. Wouldn't it be cool if your favourite URL shortener hooked up with them so that every link they shortened was pushed into the IA index? It could be done live or after a few weeks delay, if necessary. The IA could then offer a permified version of the short URL, along the lines of

http://www.archive.org/surl/*/http://bit.ly/aujkzd [non-functioning entirely mythical link]Knowing just the short URL it will be easy to find the original target URL (if it still exists!) There's also a nice bit of added value: the Wayback Machine, one of the Internet Archive's greatest pieces of self-preservation, snapshots sites periodically and the short links (being, hopefully, timestamped) could be tied to these snapshots, so that you could skip to how a page looked when the short link was minted. They might even find that the submission of short links was a guide to popularity they could use in selecting pages to archive.

OK, so the Internet Archive itself maybe isn't forever, but it's been around a while and looks good for a while longer, it's trusted, and it's neutral. Perhaps Bitly, Google, tr.im, TinyURL and all the rest might think about working with the IA so we can all feel a little more sanguine about the short links we're constantly churning out? It would certainly make me choose one provider over another, which is the sort of competitive differentiator they might take note of.

Saturday, August 21, 2010

No decisions without value/s

"Facts", in principle, are established by gathering objective evidence. Decisions, on the other hand, are the reverse: they always involve value. Value, whilst it can be a purely emotional response (a desire for something, or a positive feeling towards it), can also be transformed into values (not the same thing), which in a sense provide a template for valuing a given phenomenon. In other words, value is the outcome of an assessment, whilst values are a tool that for making that assessment.

Further, values (the tool/template) may be the internal values of an individual, perhaps embedded sub-consciously in a decision or even somatic ("instinctual", if you like, though that's a debate to avoid); or they may the externalised values embodied as a set of rules guiding a decision. This ostensibly makes the decision objective, but only by removing the value judgement into an earlier stage of the decision-making: the framing stage, where the rules for the decision are composed. These rules might even be ossified into an automated process, where rules are coded as machine instructions. They may also have been distorted along the way, so that in fact the rules represent no values held by a person at all. Whichever is the case, the values of a person or a group of people have been injected at some stage in order to make a decision possible.

The push and pull of emotion are a tide that can move our internal values incessantly, and this is one reason why it is often helpful to turn values into a set of explicit rules. Another is to externalise them so that they can be discussed and referred to as law, policy, doctrine or maybe something more informal. Of course, there's a psychological cost if this then results in dissonance between the codified values and the internalised values.

So in making decisions, or trying to influence the decisions made by other people or systems, or merely trying to understand the perspective of someone who argues in a direction that you just don't get, should we focus on the facts or on the values? Should we try to gather more evidence to demonstrate that the facts are as we see them? Should we examine the values held by another party and attempt to present the facts consonantly with them? Should we even try to change the values that are so critical in turning facts into value into decisions? Well, that's a tough one. But the one thing you can't do is address value directly: value is the product of the perceived "facts" of a scenario and the process or template for assessing the value of those facts. You can address the facts, and you can address the process of assessing but it's pointless to simply state that the value is something other than the assessment itself.

Ultimately, values themselves can be shaken by enough well-aimed evidence, but these may be of a quite different category to those facts that are put together with established values in order to reach a decision. For example, the evidence or experience required to make me a Catholic and subscribe to the values of the person I heard interviewed I cannot even imagine, even though ultimately it must be possible (perhaps on the road to Damascus). On the other hand, there are some facts through which I might be persuaded that it was wrong to prevent that particular charity from handling adoptions as it chose - for example, if it were the only agency in the country and the result of this decision was that there would be no adoption agencies at all, I might (might) feel, for purely pragmatic reasons, that it would be better to let them carry on even if that meant living with their discriminatory policy. Thankfully that's not the situation!

I don't know if this framework I've outlined is useful or right. I'm not a psychologist, a philosopher or a logician. Perhaps there are people out there who have very different ways of making decisions and this model of splitting out values from assessments of value doesn't work for them. I myself can see complications in examining the adoption agency question, which is nothing if not a clash of values. For my research into the role of decision making in digital sustainability, though, I think it may be a useful distinction to make, extending the insights given by Lessig's modalities of regulation (PDF) (this is typically looked at as a legal theorem but it's really about the "regulation" of decisions).

*yes, I know

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Posted elsewhere: Pecker up, Buttercup

Incidentally, your pecker is your nose.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

All change for the Imperial War Museum

I delayed this post a while whilst the paperwork got sorted out, but it's not been a secret for quite a while that I'm leaving the Museum of London next month (like, I told the world here). However even today a friend at work came up to me and whispered "I heard you're leaving", so for those other friends I've somehow not managed to tell, well, it's true.

It was 8 years ago in January that I began here in my first paid museum job, though I'd never imagined working with computers before starting my Museum Studies MA. It's very much time to leave now, and as luck would have it the perfect opportunity for me turned up at the right time - or as close to the right time as I could reasonably hope! After all, good digital media jobs in museums don't turn up all that often, and if you're looking for a little extra responsibility the choices are fewer still.

Which makes me feel all the more fortunate to have been given the chance to work as Technical Web Manager at the Imperial War Museum. I will be working for Carolyn Royston, who steered the huge and hugely challenging National Museums Online Learning Project through. She was appointed a year ago by the then-recently-installed director, Diane Lees, and since then she's been busy planning how to "put digital at the heart of the museum", assessing what the IWM has and how to move forward, and building a team fit for purpose. I feel lucky to be about to become a part of that digital team, which benefits from a strong vision and backing at the most senior level - not to mention an exceptional collection (both "real" and digitised).

My role, as I understand it (and I guess being new it will evolve plenty) will be some combination of programming and planning, developing a technical strategy to compliment the overall digital strategy, specifying infrastructure and so on. The IWM has some of key factors in place already (a decent DAMS, recently centralised collections databases), but the opportunities are plentiful for doing something fresh. I know that it also has a team of people that are itching to make that happen and I'm so looking forward to getting to know them and finding my place beside them.

I can't leave it at that without also saying how sorry I am to be leaving my friends at the Museum of London. I'm going to miss them. We have been through some real trials but somehow, despite unfair winds, we have managed to do some pretty good stuff, I think. I also regret having to take my leave at this exact point in time (well, in May) before I can fully see out two of the most significant projects I have been part of, and without a single in-house web developer to hand over to. I know that this will make life difficult for some of my most valued colleagues (as well as for the people who are responsible for the previous statement being true).

But whilst a couple of things may have to, well, not happen or not happen for some time, I should be around long enough to see our Collections Online system completed. If not then it won't be far off (thanks to Knowledge Integration), and the first public interface for it in our glorious new Galleries of Modern London should be in testing (thanks to Precedent).

So with only limited handover possible, I'm spending the last few weeks working on this project and wrapping up a few things that have been hanging on forever. Fingers crossed I can leave a few people happy that yes, it finally did get done.

Friday, March 19, 2010

Did I never blog this? Eejit! Here's the LAARC API

I think I'd meant to do a big explanatory post and since I didn't get round to that just never mentioned it. So for now I'll just get the word out and say, this is the work of Julia Fernee who re-engineered the whole back-end of the LAARC system to make it work sweetly, fixed stuff broken by a change to Mimsy XG, got digital downloads behaving again and ironed out various other un-noticed bugs. Ultimately it's all still based on the work of Sarah Jones and later Mia Ridge, but Julia's work now puts the database in a place where we can build from. Play with the API and let us know what you think.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

LIDO references

So anyway, if you're looking for a way in to LIDO, here are a couple of good references:

- Introduction to LIDO by Regine Stein (a slideshow for a workshop giving the background and fundamentals of LIDO. PDF)

- LIDO - Lightweight Information Describing Objects (the specification as at 11/20009. PDF)

- CIDOC CRM Mappings, Specializations and Data Examples (includes a link to a Word doc explaining the mapping of LIDO to the CRM)

BTW I have now added these to Delicious the manual way: http://delicious.com/jottevanger/lido

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Linked Data meeting at the Collections Trust

[UPDATE, March 2010: Richard Light's presentation is now available here]

On February 22nd Collections Trust hosted a meeting about Linked Data (LD) at their London Bridge offices. Aside from yours truly and a few other admitted newbies amongst the very diverse set of people in the room, there was a fair amount of experience in LD-related issues, although I think only a few could claim to have actually delivered the genuine article to the real world. We did have two excellent case studies to start discussion, though, with Richard Light and Joe Padfield both taking us through their work. CT's Chief Executive Nick Poole had invited Ross Parry to chair and tasked him with squeezing out of us a set of principles from which CT could start to develop a forward plan for the sector, although it should be noted that they didn’t want to limit things too tightly to the UK museum sector.

In the run-up to the meeting I’d been party to a few LD-related exchanges, but they’d mainly been concentrated into the 140 characters of tweets, which is pragmatic but can be frustrating for all concerned, I think. The result was that the merits, problems, ROI, technical aspects etc of LD sometimes seemed to disappear into a singularity where all the dimensions were mashed into one. For my own sanity, in order to understand the why (as well as the how) of Linked Data, I hoped to see the meeting tease these apart again as the foundation for exploring how LD can serve museums and how museums can serve the world through LD. I was thinking about these as axes for discussion:

- Creating vs consuming Linked Data

- End-user (typically, web) vs business, middle-layer or behind-the-scenes user

- Costs vs benefits. ROI may be thrown about as a single idea, but it’s composed of two things: the investment and the return.

- On-the-fly use of Linked Data vs ingested or static use of Linked Data

- Public use vs internal drivers

To start us off, Richard Light spoke about his experiments with the Wordsworth Trust’s ModesXML database (his perennial sandbox), taking us through his approach to rendering RDF using established ontologies, to linking with other data nodes on the web (at present I think limited to GeoNames for location data, grabbed on the fly), and to cool URIs and content negotiation. Concerning ontologies, we all know the limitations of Dublin Core but CIDOC-CRM is problematic in its own way (it’s a framework, after all, not a solution), and Richard posed the question of whether we need any specific “museum” properties, or should even broaden the scope to a “history” property set. He touched on LIDO, a harvesting format but one well placed to present documents about museum objects and which tries to act as a bridge between North American formats (CDWALite) and European initiatives including CIDOC-CRM and SPECTRUM (LIDO intro here, in depth here (both PDF)). LIDO could be expressed as RDF for LD purposes.

For Richard, the big LD challenges for museums are agreeing an ontology for cross-collection queries via SPARQL; establishing shared URLs for common concepts (people, places, events etc); developing mechanisms for getting URLs into museum data; and getting existing authorities available as LD. Richard has kindly allowed me to upload his presentation Adventures in Linked Data: bringing RDF to the Wordsworth Trust to Slideshare.

Joe Padfield took us through a number of semantic web-based projects he’s worked on at the National Gallery. I’m afraid I was too busy listening to take many notes, but go and ferret out some of his papers from conferences or look here. I did register that he was suggesting 4store as an alternative to Sesame for a triple store; that they use a CRM-based data model; that they have a web prototype built on a SPARQL interface which is damn quick; and that data mining is the key to getting semantic info out of their extensive texts because data entry is a mare. A notable selling point of SW to the “business” is that the system doesn’t break every time you add a new bit of data to the model.

Beyond this, my notes aren’t up to the task of transcribing the discussion but I will put down here the things that stuck with me, which may be other peoples’ ideas or assertions or my own, I’m often no longer sure!

My thoughts in bullet-y form

I’m now more confident in my personal simplification that LD is basically about an implementation of the Semantic Web “up near the surface”, where regular developers can deploy and consume it. It seems like SW with the “hard stuff” taken out, although it’s far from trivial. It reminds me a lot of microformats (and in fact the two can overlap, I believe) in this surfacing of SW to, or near to, the browsable level that feels more familiar.

Each audience to which LD needs explaining or “selling” will require a different slant. For policy makers and funders, the open data agenda from central government should be enough to encourage them that (a) we have to make our data more readily available and (b) that LD-like outputs should be attached as a condition to more funding; they can also be sold on the efficiency argument or doing more with less, avoiding the duplication of effort and using networked information to make things possible that would otherwise not be. For museum directors and managers, strings attached to funding, the “ethical” argument of open data, the inevitability argument, the potential for within-institution and within-partnership use of semantic web technology; all might be motives for publishing LD, whilst for consuming it we can point to (hopefully) increased efficiency and cost savings, the avoidance of duplication etc. For web developers, for curators and registrars, for collections management system vendors, there are different motives again. But all would benefit from some co-ordination so that there genuinely is a set of services, products and, yes, data upon which museums can start to build their LD-producing and –consuming applications.

There was a lot of focus on producing LD but less on consuming it; more than this, there was a lot of focus producing linkable data i.e. RDF documents, rather than linking it in some useful fashion. It's a bit like that packaging that says "made of 100% recyclable materials": OK, that's good, but I'd much rather see "made of 100% recycled materials". All angles of attack should be used in order to encourage museums to get involved. I think that the consumption aspect needs a bit of shouting about, but it also could do with some investment from organisations like Collections Trust that are in a position potentially to develop, certify, recommend, validate or otherwise facilitate LD sources that museums, suppliers etc will feel they can depend upon. This might be a matter of partnering with Getty, OCLC or Wikipedia/dbPedia to open up or fill in gaps in existing data, or giving a stamp of recommendation to GeoNames or similar sources of referenceable data. Working with CMS vendors to make it easy to use LD in Modes, Mimsy, TMS, KE EMu etc, and in fact make it more efficient than not using LD; now that would make a difference. The benefits depend upon an ecosystem developing, so bootstrapping that is key.

SPARQL: it ain’t exactly inviting. But then again I can’t help but feel that if the data was there, we knew where to find it and had the confidence to use it, more museum web bods like me would give it a whirl. The fact that more people are not taking up the challenge of consuming LD may be partly down to this sort of technical barrier, but may also be to do with feeling that the data are insecure or unreliable. Whilst we can “control” our own data sources and feel confident to build on top of them, we can’t control dbPedia etc., so lack confidence of building apps that depend on them (Richard observed that dbPedia contains an awful lot of muddled and wrong data, and Brian Kelly's recent experiment highlighted the same problem). In the few days since the meeting there have been more tweets in this subject, including references to this interesting looking Google Code project for a Linked Data API to make it simpler to negotiate SPARQL. With Jeni Tennison as an owner (who has furnished me with many an XSLT insight and countless code snippets) it might actually come to something.

Tools for integrating LD into development UIs for normal devs like me – where are they?

If LD in cultural heritage needs mass in order for people to take it up, then as with semantic web tech in general we should not appeal to the public benefit angle but to internal drivers: using LD to address needs in business systems, just as Joe has shown, or between existing partners.

What do we need? Shared ontologies, LD embedded in software, help with finding data sources, someone to build relationships with intermediaries like publishers and broadcasters that might use the LD we could publish.

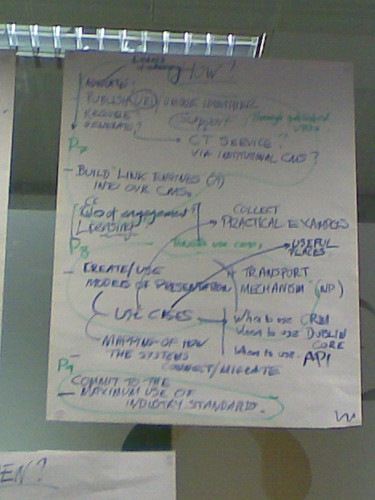

Outcomes of the meeting

So what did we come up with as a group? Well Ross chaired a discussion at the end that did result in a set of principles. Hopefully we'll see them written up soon coz I didn't write them down, but they might be legible on these images: